This Moment is Everything

or where I put my psychic energy 1982-1987

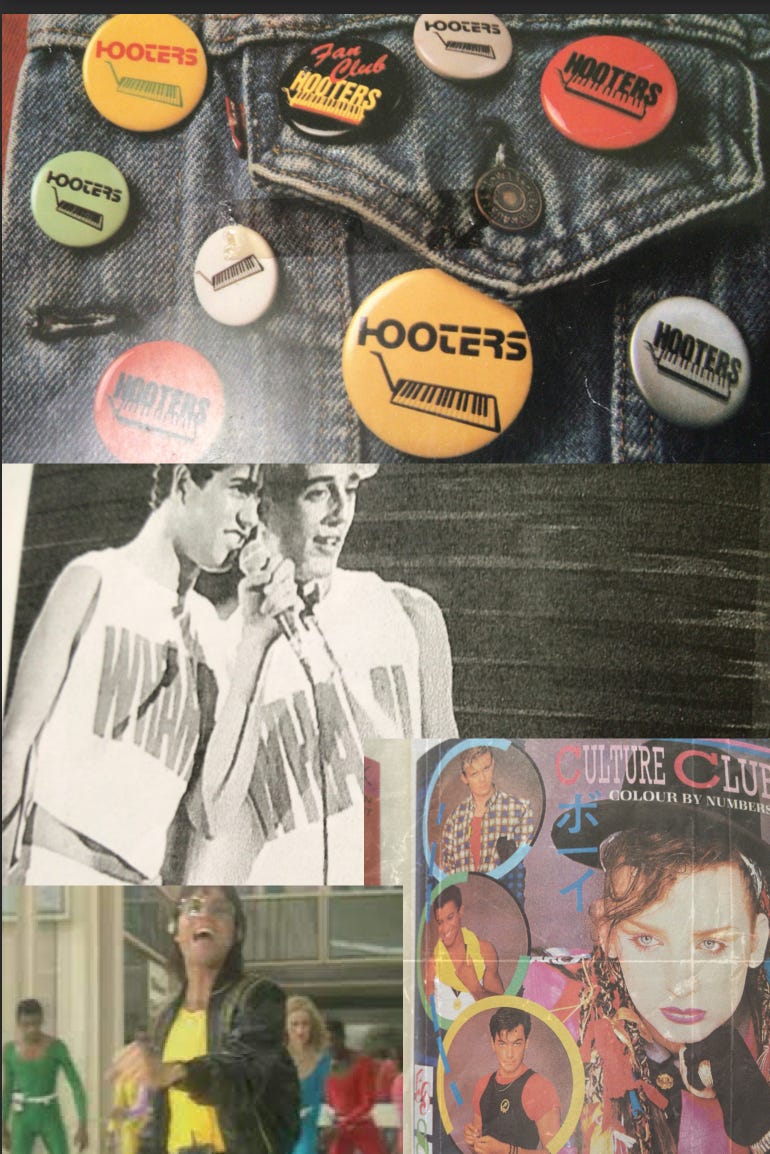

It was New Year’s Eve, on maybe the last serious family holiday. My older sisters and I were watching a band play at a park by the ocean. This band wasn’t anyone, just locals, but we were enchanted. We danced, we got giddy, we sang along to Wild Thing. The girls on back-up vocals had short skirts and asymmetrical haircuts, they looked like the girls in The Human League— so cool! Afterwards we hung around, not wanting the night to be over. We talked to the singer. We talked all over him. This was the beginning.

Music was becoming so important to us, we wanted to climb inside it. To know the bands from afar was not enough, we had to meet them. A film cycling on TV at the time was I Wanna Hold Your Hand. It was about a bunch of teenagers trying to get in to see the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show. In my favourite scene, prim Nancy sneaks into the band’s hotel room. When she hears them coming she hides behind a food-trolley. She watches their matching pants-legs and winkle-pickers, and eavesdrops on their Liverpudlian prattle. Finally they leave and she re-emerges to drift around in ecstacy, touching their things, draping herself across John’s guitar. Those who lack the fan gene will never understand this idea, that someone’s brilliance can be transferred to their belongings, and that by touching them, you might siphon off some of that shine for yourself, but I was always getting lessons from television, and this felt profound.

According to cultural theorist Henry Jenkins, being a fan means taking a subordinate position within a cultural hierarchy. Fandom can be transgressive as it requires putting energy into something generally unappreciated by ‘high culture’ institutions. It’s a social identity, a way of belonging, but, Jenkins writes, “Nobody can live permanently in this utopia, which becomes recognizable as such only against the backdrop of mundane life; fans must come and go from fandom, finding this “weekend only world” where they can, enjoying it for as long as possible, before being forced to return to the workaday world.”1

My parents were perfect examples of what it meant to commit to the workaday world. Both had full time jobs at universities, and seemed less than ecstatic about it. As a kid I occasionally went into work with them. I remember grey, brutalist buildings, a feeling of haste: no joy, no fun. It was a black and white world. And then there was Wham! on TV singing in ‘Wham Rap!’ I ain’t never gonna work, get down in the dirt, I choose to cruise …How could I align myself with anything else?